הרבי מלובביץ’ והרב אריה קפלן משחזרים “מדיטציה יהודית”:

האם “המדיטציה” היא המצאה בלעדית של המזרח הרחוק? או שמא גם לנו יש מסורת של מדיטציה מעשית?

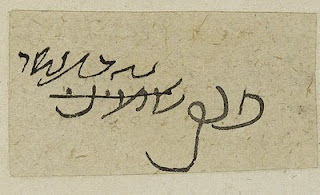

שאלה זו התחילה להתעורר לפני כשלושים שנה כאשר יהודים רבים התחילו לתרגל מדיטציות שמקורן בבודהיזם ובהינדואיזם. נהירת אלפי יהודים למדיטציה טרנסצנדנטאלית (מ”ט) הביאה את הרבי מלובביץ’, רבי מנחם מנדל שניאורסון (1994-1902), לפנות לפסיכולוגים ורופאים שיציעו אלטרנטיבה כשירה. בתאריך ט”ז אדר א תשל”ח (23 פברואר 1978) הציע הרבי לד”ר יהודה לנדס, שהתגורר אז בקליפורניה, לגייס קבוצת רופאים המתמחים בנוירולוגיה ופסיכיאטריה כדי לאמץ טכניקות מדיטציות כשירות בעלות ערך תרפויטי להרפיה ושחרור ממתח נפשי. אחר כך, בהתוועדות פומבית, בתאריך י”ג תמוז תשל”ט (8 ביולי 1979), הסביר הרבי שאבותינו בחרו במקצועות כמו רועי צאן כדי שיוכלו להקדיש זמן להתבודדות בשדות ולא להיות בחיים הרועשים שבעיר. הרבי דרש שמדיטציה יהודית תהיה מיועדת לא רק להתבוננות בגדולת ה’ ובשפלות האדם אלא גם להרפיה נפשית. לטענתו, בכניסה להתבודדות, ניתן להגיע לשלווה ולבריאות נפשית ולהשיג יישוב הדעת.

באותן השנים התחיל הרב אריה קפלן (1983-1935) לאסוף ולפענח מגוון רחב של שיטות מדיטציה ממקורות היהדות. טענתו המרכזית הייתה ש”מדיטציה” בשמותיה העבריים (התבודדות, התבוננות, ייחוד וכוונה) היא מסורת בת אלפי שנים שבה עסקו אבותינו, נביאינו ומקובלינו. לשיטתו, הפנומנולוגיה והפסיכולוגיה של מדיטציה יהודית אינה שונה משיטות מדיטציה אחרות, אך נבדלת היא במטרות ובתוצאות. בספרו “מדיטציה והתנ”ך” (1978) ביקש ר’ קפלן לאושש את טענתו שהנביאים הגיעו לחוויית הנבואה שלהם “במצב של מדיטציה”. לפי שחזורו, בתקופת המקרא “למעלה ממיליון איש” עסקו במדיטציה והתלמידים שנקראו “בני נביאים” תרגלו ב”בתי ספר למדיטציה”. מסקנתו שהמדיטציה הייתה דרך חשובה ביותר להגיע לנבואה, הארה והתגלות השפיעה רבות על הבאים אחריו לבחון מחדש את אופיין של שיטות המדיטציה הקדומות. ספרו ‘מדיטציה וקבלה’ (1982) הוא אוסף עשיר של מקורות ראשוניים עם הצעות פירוש של טכניקות המדיטציה מספרות ההיכלות והזוהר, וממקובלים ספרדיים כמו ר’ יוסף ג’יקטילה ור’ יצחק דמן עכו. אחד החידושים הרבים הוא שחזור שיטת מדיטציה של ר’ יצחק סגי-נהור ותלמידיו ר’ עזרא ור’ עזריאל מגירונה. הרב קפלן הקדיש פרק שלם לשיטת ר’ אברהם אבולעפיה, שני פרקים למקובלי צפת (הרמ”ק, האר”י ור’ חיים ויטאל), ופרק למורי החסידות מהבעל שם טוב עד לר’ נחמן מברסלב. אפשר לחלוק על השחזורים של הרב קפלן, אך התעוזה לפרש את המקורות פותחת שאלה שכמעט ולא נדונה: מה היו ‘השיטות’ של אבות האומה והנביאים, והאם נכון לפענחן כטכניקות במדיטציה? בספרו האחרון, ‘מדיטציה יהודית – מדריך מעשי’ אותו סיים הרב קפלן בדצמבר 1982, זמן קצר לפני מותו, הוא פרש קשת רחבה של שיטות במדיטציה יהודית החל מהדמיה, שימוש במנטרות והתבוננות. בעקבות כתבי ר’ קפלן התפרסמו ספרים רבים ואתרי אינטרנט שונים לבירור השיטות במדיטציה יהודית ולחידושן.

דרך מדיטטיבית ליישוב הדעת ולהשגה נבואית

היכן אפשר למצוא “מדיטציה” במקורות היהדות?

התקדים המפורסם ביותר הוא במסכת ברכות, פרק ה, משנה א: חֲסִידִים הָרִאשׁוֹנִים שהָיוּ שׁוֹהִין שָׁעָה אַחַת וּמִתְפַּלְּלִין כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּכַוְּנוּ אֶת לִבָּם למקום. החסידים הראשונים פעלו מהמאה הראשונה לפנה”ס עד לסוף התקופה התלמודית, במיוחד באזור הגליל, והיו ידועים בכוח תפילתם. המפורסמים ביניהם: חוני המעגל, רבי חנינא בן דוסא ור’ פינחס בן יאיר.

מה עשו החסידים הראשונים לפני התפילה? כיצד התכוננו וכיוונו את לבם?

על בסיס משנה זו פותחה מסורת מדיטטיבית בימי הביניים. מקובלי גירונה, ובראשם ר’ יצחק סגי נהור (1235-1160), הבינו שהחסידים הראשונים ביקשו למשוך את האור העליון ולהגיעה להשגה נבואית. ר’ עזרא מגירונה הסביר כיצד לשחזר את “מסורת החכמה היא ידיעת השם” שנמסרה ממשה רבינו לאורך הדורות עד לרבי עקיבא וחביריו שנכנסו לפרדס והיו דורשין במעשה המרכבה. רק בגלל חשכת הגלות “פסקה החכמה הזאת מישראל” ו”החסידים ואנשי מעשה חדלו” (פירוש לשיר השירים, עמ’ תעח-תעט). ר’ עזריאל מגירונה תיאר כיצד “החסידים הראשונים היו מעלים מחשבתם עד מקום מוצאה”, ומזכירים סודות עליונים של הספירות, ו”הדברים מתברכים ומתוספים ומתקבלים מאפיסת המחשבה כאדם הפותח בריכת מים ומתפשטת אילך ואילך”. “איפוס” המחשבה מאפשר זרימת השפע ומשיכת האור. וכך גם כתוב בחיבור “איגרת הקודש” (שנכתב בידי ר’ עזרא מגירונה או ר’ יוסף ג’יקטיליה): “חסידים הראשונים מדביקין המחשבה בעליונים, ומושכין מאור העליון למטה, ומתוך כך היו הדברים מתווספים ומתברכין כפי כוח המחשבה”. מקובלי ספרד במאה הי”ד, ר’ מנחם רקנאטי והמחבר האנונימי של ספר “מערכת האלוהות”, הזכירו באהדה שיטה מדיטטיבית זאת.

במקביל לפיתוח המדיטציה הקבלית בספרד, התפתחה מסורת מדיטטיבית בספרות ההלכתית שהייתה מבוססת על דברי הרמב”ם. הרמב”ם בפירושו למשנה במסכת ברכות פירש שהחסידים הראשונים היו מיישבים דעתם ומשקיטים את המחשבות כהכנה לתפילה. רעיון זה קיבל צורה הלכתית נורמטיבית בניסוחו של ר’ יעקב בן הרא”ש ב”טור”, ובעקבותיו על-ידי ר’ יוסף קארו ב”שולחן ערוך”, “אורח חיים”, הלכות תפילה, סימן צ”ח. האידיאל בהתכוונות הוא כדוגמת ההתבודדות של החסידים הראשונים: “ויעיר הכוונה ויסיר כל המחשבות הטורדות אותו עד שתישאר מחשבתו וכוונתו זכה בתפילתו… וכן היו עושין חסידים ואנשי מעשה שהיו מתבודדים ומכוונין בתפילתן עד שהיו מגיעים להתפשטות הגשמיות ולהתגברות רוח השכלית עד שהיו מגיעים קרוב למעלת הנבואה”.

מה היו ההוראות המעשיות של הרמב”ם לתרגול המדיטטיבי?

ב”מורה נבוכים”, ג,נ”א הדריך הרמב”ם את הקורא בתרגול מעשי של התבודדות החושים בדומה לתרגילים שהיו מוכרים בתקופתו במדיטציה המוסלמית אצל אלגזאלי, אבן רושד, אבן באג’ה ואבן טופיל. פרק נ”א הוגדר על-ידי פרשני “המורה”, האפודי ושם טוב אבן שם טוב, בשם “הנהגת המתבודד”. מטרת הפרק היא להגיע לשלמות נבואית. הדרכת הרמב”ם היא לכוון את המחשבות בעזרת שיטת “התבודדות”, לבודד את החושים, ולקלוט את השפע האלוהי הן בכוח השכלי והן בכוח המדמה. תחילה יש לתרגל כוונה ב”התרוקנות” המחשבות “מכל דבר” זולת אהבת ה’ ויראתו. אח”כ יש להשתמש בפסוקים כמצפן להכוונת המודעות בדומה לתפישות מודרניות ידועות כגון מיינדלפולנס Mindfulness בשיטת ויפָּסָנָה, תפילה ממורכזת (Centering Prayer) בנצרות, ומדיטציית ההתבוננות (Contemplative Meditation).

ר’ אברהם בנו של הרמב”ם המשיך את דרכו המדיטטיבית של אביו. הוא ביקש להראות שבמסורת ישראל החל מאבות האומה, הייתה ההתבודדות הפנימית דרך להשגת הנבואה. בספרו “ספר המספיק לעובדי ה’” הבחין ר’ אברהם בין התבודדות חיצונית כהתרחקות מהחברה לעומת התבודדות פנימית בה מרחיקים מחשבות שאינן רצויות כדי ליצור “טיהור הלב וזיכוכו מכל דבר זולתו יתעלה” והוא תיאר את ההתבודדות הפנימית כמדרגה העליונה בסולם ההתגלות. בפירושו לתורה הסביר ר’ אברהם כיצד השגת הנביאים כרוכה בהתבודדות “המאחדת” את האדם עם קונו. התהליך מתקיים “בביטול פעולות החלק המרגיש של הנפש, בהרחקת החלק הדוחף מהתעסקות בענייני העולם הזה, ובהעסקת החלק השכלי בענייני האלוהות”. שיטות אלה השפיעו על הפרשנות המדיטטיבית-מיסטית לכתבי הרמב”ם שפותחו אצל מקובלי ספרד במאה הי”ג במיוחד אצל ר’ אברהם אבולעפיה ועל כך ראוי להרחיב במאמר נפרד.

ההדרכה המדיטטיבית של ר’ חיים ויטאל בצפת במאה הט”ז

נדלג עכשיו לצפת של המאה הט”ז. ר’ חיים ויטאל (רח”ו) (1542- 1620), תלמידם הדגול של האר”י והרמ”ק, אסף ותיעד עשרות שיטות במדיטציה יהודית. בספרו “שערי קדושה” ביקש רח”ו להורות את הדרך להורדת השפע האלוהי ולהשגת רוח הקודש. ההנחיה היא: “יתבודד במחשבה” תוך שקט חיצוני ופנימי, “ויפשיט מחשבתו מכל ענייני העולם הזה כאילו יצאה נפשו ממנו, כמת שאינו מרגיש כלל”. תוך מצב תודעה זה ניתן לפתוח את המודעות ו”להתדבק שם בשורש נשמתו ובאורות עליונים”, לעשות “ייחודים” של שמות הוויה להמשכת האור וה”שפע בכל העולמות”, וגם לקבל את “חלקו האישי” הייחודי בשפע. במבוא ל”שערי קדושה”, סוקר רח”ו את תולדות החיפוש לדבקות, רוח הקודש ונבואה. הוא מתאר כיצד ביקשו החסידים הראשונים להתבודד “עד אשר תדבק מחשבתם בכוח וחשק נמרץ באורות העליונים. והתמידו בכך כל ימיהם עד אשר עלו למדרגת רוח הקודש, וַיִּתְנַבְּאוּ וְלֹא יָסָפוּ (במדבר י”א, כה)”. בספרו “שערי קדושה” מפרט רח”ו את ההדרכה להגיע לרוח הקודש. בחלק הרביעי אסף רח”ו כתריסר שיטות מדיטטיביות “אשר על ידם יושג רוח הקודש, כאשר בחנתי וניסיתי ונתאמתו על ידי”. המדפיס בקושטא, בשנת 1734, סבר שאין להדפיס את הסודות שבחלק הרביעי, וכך כשלושים מהדורות נדפסו בלי החלק הרביעי. היום יש לנו את הטכסים של חלק ד, ואפשר ללמוד על שיטות המדיטציה של הרמב”ן, ר’ מנחם רקנאטי, ר’ יהודה חייט, ר’ יצחק דמן עכו (שיטת ההשתוות) ו”שער הכוונה למקובלים הראשונים”. רח”ו נותן פירוט להתבודדות בהדמיה של עלייה לשמים, ושינון אמירה מהמשנה עד שהתנא מדבר מפי בעל הסוד והמתבודד יבחין במסר רוחני. הוא מביא את צירופי האותיות מר’ אברהם אבולעפיה ב”ספר החשק” ו”חיי עולם הבא”, וההתבוננות בשם הוויה המורכב מ-72 אותיות הנובע משלושה פסוקים בשמות י”ד,יט-כא. בקיצור, אצל רח”ו נאסף מבחר גדול של שיטות במדיטציה יהודית שמטרתן המשותפת היא השגת דרגות רוחניות גבוהות.

מדיטציה חסידית מר’ אלימלך מִלִּיזֶענְסְק לאדמו”ר מפיאסצ’נה

ההתעוררות המעשית למדיטציה יהודית התחילה שוב במאה הי”ח מתוך הדגשים בחסידות הבעש”ט של כוונות פנימיות, טיהור הלב, ופיתוח רגשי-אמוני של אהבה, שמחה ויראה. כך למשל, ר’ אלימלך מִלִּיזֶענְסְק (1787-1717), ביקש לפני התפילה: תְּהֵא מַחְשְׁבותֵֹינוּ זַכָּה צְלוּלָה וּבְרוּרָה וַחֲזָקָה בֶּאֱמֶת וּבְלֵבָב שָׁלֵם. הוא נימק זאת בספרו “נועם אלימלך”: “חסידים הראשונים היו שוהים שעה אחת וכו’, וכוונתם הייתה כדי לזכך ולטהר את מחשבתם ולדבק עצמם בעולמות עליונים עד הגיעם קרוב להתפשטות הגשמיות כמבואר ב”שולחן ערוך”, “אורח חיים”. האדמו”ר מפיאסצ’נה, הרב קלונימוס קלמיש שפירא (1889-1943), הסתמך על הכוונות המדיטטיביות של ר’ אלימלך להדגיש את החשיבות ביצירת מחשבה זכה וצלולה. בספרו “דרך המלך”, בראשית, עמ’ ד-ה ביאר: “וחֲסִידִים הָרִאשׁוֹנִים הָיוּ שׁוֹהִים שָׁעָה אַחַת קודם התפילה, להתעורר למעלה מן הדיבור בכלל, ובדברם אחר כך דיבורי התפילה היו מורידים את אור האצילות והתעוררות אהבה ויראת ה’ ותפארת של אצילות גם לדבריהם, אף לדברי התפילה של צרכי עוה”ז, ובכל העולמות האירו אור עליון, והכל היה לשם ה’”. הסוד לפי האדמו”ר הוא לגלות את העניין האלוהי הטמון בקרב האדם למעלה מן הדיבור, המחשבה והרצון המוכרים בדרך כלל. האדם עסוק במחשבותיו בטרדות כיצד יתפרנס, מה יעשה מחר, איך יתכבד וכיו”ב, ועל-ידי השתקת המחשבות, הוא יכול לגלות את האהבה והיראה הטהורה “של בחינת אצילות שלו”. האדמו”ר רומז לדרך מדיטטיבית להשתיק את המחשבות. השיטה דומה במהותה לטכניקות שהיו קיימות בימיו אצל בני דורו, ג”א גורדייף (1949-1866) ופ”ד אוספנסקי (1947-1878). אך שיטת האדמו”ר הינה חסידית במובהק. ההדרכה מתחילה בהתבוננות פנימית בתנועת המחשבות, “התרוקנות הראש”, ועצירת המחשבות “משטפן הרגיל”. המטרה הראשונית היא סילוק המחשבות הטורדניות, ביטול האנוכיות מול האין סוף, והשתחררות מה”אני” העסוק בהתרכזות של חשיבה קוגניטיבית. אפשר להשקיט את זרם המחשבות ו”לבוא בהקיץ” למצב מנטאלי הדומה לרגיעה שבשינה. ייתכן שמדובר בתופעה דומה למה שמכונה במצבי תודעה בשם היפנאגוגיה, דהיינו מצב של “נים ולא נים” המוכר כאזור של דמדומים במעבר מערנות לשינה. ההשקטה יוצרת מצב של “חלום אחד משישים בנבואה”, כלומר אפשרות מעין נבואית לקבלת ההשראה ממרום. אל תוך השקט הפנימי הזה יש להכניס מחשבות של קדושה, ולחזק “אמונה או אהבה ויראה”. ניתן לחוש קרבה לה’ ולהשתמש בהשקטה לתיקוני המידות. בעזרת תרגול ממושך בהשקטה ניתן להרגיש אמונה בה’ בבחינת זֶה אֵלִי וְאַנְוֵהוּ (שמות ט”ו,ב). האדמו”ר היה מוסיף ניגון מיוחד לפסוק הוֹרֵנִי ה’ דַּרְכֶּךָ, אֲהַלֵּךְ בַּאֲמִתֶּךָ יַחֵד לְבָבִי לְיִרְאָה שְׁמֶךָ. (תהילים פ”ו,יא).

מאתר מדיטציה יהודית, כאן.