בחודש האחרון התאבדו ארבעה אבות בתהליכי גירושין ואבות גרושים שנוכרו מילדיהם. ד”ר רונית דרור על התופעה המושתקת של המדינה.

בשבועות האחרונים בכל פעם שאני פותחת את הפייסבוק אני מתוייגת בפוסט על עוד אבא שהתאבד. אני מקבלת הודעות על משפחות שרוצות לשוחח איתי. השבוע פנה אליי אח של אבא נוסף שסיפר לי שהם רק קמו משבעה. הוא השאיר אחריו שני ילדים. בשבוע שעבר סיפרה לי חברה, עובדת סוציאלית, על בן משפחתה שהתאבד. לפני שבועיים התאבד אב מהישוב אלעד. לפני פחות מחודש התאבדו שני אבות מהדרום. אחד מבאר שבע והשני מישוב קטן שלא ארצה לחשוף. לכל אחד מהאבות האלו ילדים שנותרו יתומים. כל אחד מהאבות האלה הוא בן למשפחה נורמטיבית וחמה. כולם אנשים מלח הארץ. נקודה.

מדובר בסוד האפל והנורא של החברה הישראלית היום. סוד גלוי לרבים שלא נוקפים אצבע על מנת למנוע אותו. מערכות שלמות משתפות פעולה עם נשים שבידן כוח בלתי סביר על מנת להתעלל בבני זוגן בהליכי גירושין קשים מנשוא. ואכן, בישראל מדווחים גברים רבים כי הם עוברים את תהליך הגירושין כמסלול ייסורים בלתי נסבל המגובה בחוקים פוגעניים וחד צדדיים.

החל מתלונות שווא במשטרה שבדרך כלל גורמות להרחקה מיידית של האב מהילדים ומהבית מבלי לבדוק את נכונות או אמיתות הדברים. צווי הרחקה לשבוע במעמד צד אחד הניתנים בבית המשפט וצווי הגנה להרחקה לשלושה חודשים ויותר. חקירות. מעצרים. התמודדות עם האשמות על אלימות/פגיעות מיניות בבתי משפט. סכומי מזונות בלתי סבירים שלא מאפשרים לרבים את היכולת לכלכל את עצמם ו/או להשתקם מהגירושין. תביעות בהוצאה לפועל הכוללות סנקציות של מעצרים, שלילת רישיון נהיגה, עיכובי יציאה מהארץ ועוד.

תיוג מסוכן

גבר שהיה אב נורמטיבי לחלוטין רגע לפני שהתגרש, הופך באחת מסוכן, חסר מסוגלות הורית ועבריין. שלא לדבר על פגיעה בכבודם האישי והמקצועי וההתמודדות עם התפיסה החדשה של מי הם כגברים, אבות, בני זוג ובכלל כאזרחים בחברה. מצב זה הנחווה כהתמודדות עם מציאות בלתי אפשרית גורם לרבים להתמודד באופן של ‘הילחם או ברח’ בהתאם למשאבים האישיים שלהם. אבות הבורחים ומתנתקים מילדיהם נשפטים על חוסר מסוגלות ואי לקיחת אחריות בעוד שאבות הנלחמים על ילדיהם מואשמים כמסוכנים ואלימים.

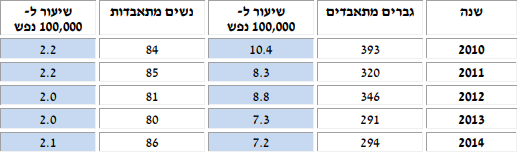

ואכן, בעשור האחרון, מאז נחשפתי לפגיעה הנובעת מהטיה מגדרית בוטה זו, ראיתי שמי שבורח ובוחר בהתאבדות הוא זה שנלחם על ילדיו ונותק מהם. נתוני מחקרים מצביעים על כך שגברים מתאבדים פי ארבעה מאשר נשים. וגברים גרושים מתאבדים פי שבעה מאשר גברים נשואים, אך מדובר בהערכת חסר כי חלקם רשומים עדיין כנשואים, פרודים או כרווקים, מאחר שהם חיו עם בת-זוג או שמדובר בגניבת זרע, שאף היא תופעה שהחלה להיות נפוצה במחוזותינו.

הדחקה ושתיקה

ההתעלמות מהתופעה הזו היא הנוראה מכולן. ההימנעות של התקשורת מפרסום התופעה ומביצוע תחקירים בנושא, היא מחדל. השתיקה של המערכות וההסכמה שילדים יוותרו יתומים בשל התאבדות אבות היא בלתי נסבלת. המשך החוקים הדרקוניים נגד גברים דוגמת חוק האיזוק האלקטרוני שחברות הכנסת נלחמות עליו, הוא אסון. האילמות של כל המערכות האמונות לדאגה על הציבור כולו, החל במשרד הרווחה, בריאות, החוק והמשפט עד התקשורת שממלאה את פיה מים כשמדובר בגברים מהווה פשע נגד האנושות.

השבוע תוייגתי גם בפוסט על אמא שהתאבדה בעקבות ניכור הורי וטיפול לקוי של המערכת. וכן, שלא יהיה ספק לאיש. יש קשר ישיר בחוסר המקצועיות בטיפול באלימות במשפחה על כל סוגייה ובעיקר בחוסר האמפתיה והאנושיות שאיבדנו עבור גברים, שללא ספק החל פוגע גם בנשים.

ד״ר רונית דרור היא פעילה למען שוויון מגדרי ומטפלת בנכי צה״ל דרך משרד הביטחון.