Have something to say? Write to Avraham Rivkas: CommentTorah@gmail.com

The Chazon Ish’s Defense of Hasagos Hara’avad

The Ra’avad’s Notes on Mishneh Torah – Substantial or Mere Polemic?

Rabbi Avraham ben David (known as Ra’avad “The Third”) wrote extensive critical emendations on nearly the whole of Maimonides’ “Mishneh Torah”. One of the most well-known aspects of the work is the tone of the comments. They tonally tend to harsh bitterness.

The question standing before us today is whether these emendations are a sustained attack on the whole of the work (and its author) or just genuine disagreement on various issues.

Let’s first look at two major examples, shall we?

Ra’avad on Mishneh Torah, Laws of Kilayim 6:1 –

וחיי ראשי לולא כי מלאכה גדולה עשה באסיפתו דברי הגמרא והירושלמי והתוספתא הייתי מאסף עליו אסיפת עם וזקניו וחכמיו כי שנה עלינו הלשונות והמליצות וסבב פני השמועות לפנים אחרים וענינים שונים כו’

He accuses Maimonides of (purposely?) distorting the Torah (or “Megaleh panim batorah [shelo kahalacha]”). And I’m no expert, but it seems the Ra’avad is also on the verge of calling for Maimonides’ excommunication for his crime…

Maimonides, Laws of Repentance 3:7 –

חמשה הן הנקראים מינים כו’ והאומר שיש שם רבון אחד אבל שהוא גוף ובעל תמונה

Five individuals are described as Minim… One who accepts that there is one Master [of the world], but maintains that He has a body or form

Ra’avad ad locum –

(והאומר שיש שם רבון אחד אלא שהוא גוף ובעל תמונה) א”א ולמה קרא לזה מין וכמה גדולים וטובים ממנו הלכו בזו המחשבה לפי מה שראו במקראות ויותר ממה שראו בדברי האגדות המשבשות את הדעות

Ra’avad seems to be saying Maimonides is among the least important of Jews…

As Kessef Mishneh (ad loc.) puts it –

כתב הראב”ד כו’. ויש לתמוה על פה קדוש איך יקרא לאומרים שהוא גוף ובעל תמונה גדולים וטובים ממנו. וכו’.

The Ohr Sameyach (the book, not the Yeshiva!) simply emends the text to read “Me’amanu \ מעמנו (from our nation)”. But no manuscript supports that correction.

Any half-serious student of “Mishneh Torah” has seen many similar comments by Ra’avad (though most are not so severe).

You have probably already decided the Ra’avad’s attacks are personal, huh? Not so fast! Yad Malachi (“Klalaei Harambam” No. 43) attempts to address the topic –

הראב”ד ז”ל בהשגותיו לא כיוון בהם למעט בכבוד הרמב”ם חלילה לרבנן קדישי כוותייהו אלא חשף הראב”ד את זרוע קדשו לחלוק עליו בכח אמיץ בכמה גופי הלכות כי היכי דלא ליסרכו כולי עלמא בתריה ללמוד וללמד בדעות מעל ספר המורה וכיוצא בו (…)

ומכאן תשובה נגד שלשלת הקבלה שכתב כי הראב”ד לא השיגו כאוהב ומבקש דעתו זולתי כאויב ומספר גנות הרמב”ם דליתא כו’

Translation: The Ra’avad in his emendations did not attempt to lessen the honor of Maimonides, perish the thought regarding such great sages. Rather he went to holy battle to disprove various Halachic views in order that the public not blindly follow Maimonides as regards his opinions in “Moreh Hanevuchim”, and the like.

This is the correct response to “Shalsheles Hakabbala” who claimed that the Ra’avad did not correct [Maimonides] as a friend, seeking out [Maimonides’] true intent, but as an enemy, and a libeler…

The Yad Malachi ends off, however, noting that the Ra’avad never even saw the “Moreh Hanevuchim”, and doesn’t ever comment on those views others found so controversial, in “Yesodei Hatorah” and the like. The opposition to the Madda might be the realm of others including Rabbenu Yechiel, Rabbenu Yona, Rabbi Meir Halevi, but not the Ra’avad.

So what’s the score so far?

What we are left with is the convincing comment by Shalsheles Hakabbala, and an attempted rebuttal demolished by its own author. The only point left in place is the sheer incongruousness of the holy Ra’avad doing any such thing. But how can we deny the evidence of our eyes?!

A better theory might be that he feared the “Mishneh Torah” would supplement the study of Gemara, or that Maimonides ought to have quoted his sources. Following is the proof-text often quoted in support of this position:

From Maimonides’ Introduction to Mishneh Torah –

ובזמן הזה תקפו הצרות יתירות, כו’. לפיכך, אותם הפירושים וההלכות והתשובות שחברו הגאונים, וראו שהם דברים מבוארים, נתקשו בימינו, ואין מבין עניניהם כראוי, אלא מעט במספר. ואין צריך לומר הגמרא עצמה, הבבלית והירושלמית, וספרא וספרי והתוספתא, שהם צריכין דעת רחבה, ונפש חכמה, וזמן ארוך, ואחר כך יוודע מהם הדרך הנכוחה בדברים האסורים והמותרים, ושאר דיני התורה, היאך הוא:

ומפני זה שנסתי מתני, אני משה בן מיימון הספרדי, ונשענתי על הצור, ברוך הוא, ובינותי בכל אלו הספרים, וראיתי לחבר דברים המתבררים מכל אלו החיבורים, בענין האסור והמותר, הטמא והטהור, עם שאר דיני התורה, כולם בלשון ברורה, ודרך קצרה, עד שתהא תורה שבעל פה כולה, סדורה בפי הכל, בלא קושיא ולא פירוק. לא זה אומר בכה וזה בכה, אלא דברים ברורים, קרובים, נכונים, על פי המשפט אשר יתבאר מכל אלו החיבורים והפירושים, הנמצאים מימות רבינו הקדוש ועד עכשיו, עד שיהיו כל הדינין גלויין לקטן ולגדול, בדין כל מצוה ומצוה, ובדין כל הדברים שתיקנו חכמים ונביאים. כללו של דבר, כדי שלא יהא אדם צריך לחיבור אחר בעולם, בדין מדיני ישראל, אלא יהא חיבור זה מקבץ לתורה שבעל פה כולה, כו’

At this time, we have been beset by additional difficulties, etc. Therefore, those explanations, laws, and replies which the Geonim composed and considered to be fully explained material have become difficult to grasp in our age, and only a select few comprehend these matters in the proper way. Needless to say, [there is confusion] with regard to the Talmud itself – both the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds – the Sifra, the Sifre, and the Tosefta, for they require a breadth of knowledge, a spirit of wisdom, and much time, for appreciating the proper path regarding what is permitted and forbidden, and the other laws of the Torah.

Therefore, I girded my loins – I, Moses, the son of Maimon, of Spain. I relied upon the Rock, blessed be He. I contemplated all these texts and sought to compose [a work which would include the conclusions] derived from all these texts regarding the forbidden and the permitted, the impure and the pure, and the remainder of the Torah’s laws, all in clear and concise terms, so that the entire Oral Law could be organized in each person’s mouth without questions or objections.

Instead of [arguments], this one claiming such and another such, [this text will allow for] clear and correct statements based on the judgments that result from all the texts and explanations mentioned above, from the days of Rabbenu Hakadosh until the present. [This will make it possible] for all the laws to be revealed to both those of lesser stature and those of greater stature, regarding every single mitzvah, and also all the practices that were ordained by the Sages and the Prophets. To summarize: [The intent of this text is] that a person will not need another text at all with regard to any Jewish law. Rather, this text will be a compilation of the entire Oral Law, etc.

A comment by Ra’avad –

א”א, סבר לתקן ולא תיקן, כי הוא עזב דרך כל המחברים אשר היו לפניו, כי הם הביאו ראיה לדבריהם, וכתבו הדברים בשם אומרם, והיה לו בזה תועלת גדולה, כי פעמים רבות יעלה על לב הדיין לאסור או להתיר, וראייתו ממקום אחד, ואילו ידע כי יש גדול ממנו, הפליג שמועתו לדעה אחרת, היה חוזר בו. ועתה לא אדע למה אחזור מקבלתי ומראייתי בשביל חבורו של זה המחבר. אם החולק עלי גדול ממני, הרי טוב, ואם אני גדול ממנו, למה אבטל דעתי מפני דעתו. ועוד, כי יש דברים שהגאונים חולקים זה על זה, וזה המחבר בירר דברי האחד וכתבם בחיבורו, ולמה אסמוך אני על ברירתו, והיא לא נראית בעיני, ולא אדע החולק עמו, אם הוא ראוי לחלוק אם לא. אין זה אלא כל קבל די רוח יתירא ביה

But that theory is altogether arbitrary. Who says this one remark is a primer and account for all his thousands of other comments?!

By the way, cf. Kessef Mishneh and others for answers to Ra’avad’s statement.

What’s going on? Is the Ra’avad truly battling Maimonides as an enemy? I have come across several contemporary authors who certainly see it that way. They denounce any and all aggressive remarks in Torah study and point to Ra’avad III as their example. “He tried to fight dirty against the Rambam (Maimonides)”, they say, “but guess what? He lost; the Rambam won. We rule like the Rambam in almost every case of a dispute between them! History has made a mockery of him. So there!”

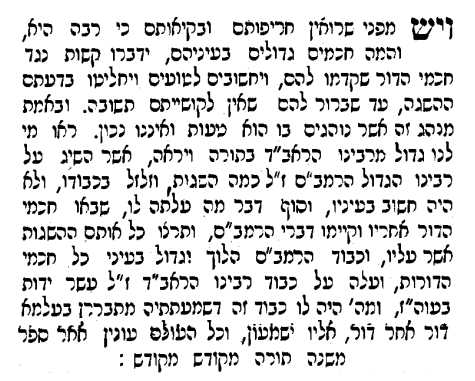

Here’s a quote from Rav Pe’alim’s introduction –

It’s time for some answers:

Writes the Chazon Ish (Yoreh De’ah 150:14) –

כל כונת הראב”ד היתה לתקן את ס’ היד שתהיינה שם כל הלכות של כל התורה מסודרות והרבה פעמים מפרש דברי הר”מ ומבארם ופעמים שמבכר דעת הר”מ על דעתו וכמש”כ בפ”ז מה’ פרה ה”ג ובפ”ה ה”ה שם, ולפיכך הוא משיג אפילו בדברים שהן בשיקול הדעת אף שיש לו לישב גם דעת הר”מ

Translation: The sole intention of the Ra’avad was to improve the [Mishneh Torah] book so that all the laws of the entire Torah would be structured within. This is why he often clarifies Maimonides’ intention and expounds it. Occasionally Ra’avad even prefers Maimonides’ view over his own. Cf. Laws of Parah 7:3, and 5:5 there. This is why he comments even on matters of subjective judgment (“Shikul Hada’as”), although [Ra’avad] could just as easily have resolved the problems in Maimonides’ view.

The Chazon Ish means to address our very problem. He demonstrates the Ra’avad’s intention was to complement the Mishneh Torah, not to demolish it.

This approach is also supported from Kessef Mishneh, Laws of Vows 1:15 –

ובאמת כי נוראות נפלאתי על אדוננו הראב”ד אשר דרכו לבא בסופה ובסערה נגד רבינו במקומות אחרים אשר תירוצם מצוי, ובמקום הזה שבקיה לרגזנותיה, ודבר בנחת לומר שאין דברים הללו מחוורים אצלו ושטעה בפירוש הגמ’ כאילו אין כאן קושיא כי אם חילוק פירוש בגמ’ ושלא נתחוור לו הפירוש ההוא, והדבר ברור לכל מעיין כי דברי רבינו מרפסין איגרא ואין להם שום קיום והעמדה ע”פ הגמ’ בשום פירוש שיפרש.

In other words, Kessef Mishneh assumes the vociferousness of the attacks to be an accurate reflection of the level of true difficulty or disagreement. Understand this well.

Regarding the part about Maimonides’ being a “lesser Jew” (per Ra’avad’s remark on the Laws of Repentance 3:7), the Chazon Ish parenthetically resolves this gracefully elsewhere (Ibidem 62:21, end) –

ומש”כ הראב”ד ז”ל [כפי נוסחת הספרים] וכמה גדולים וטובים ממנו כו’ האי “ממנו” ר”ל ממנו עם ישראל

Basically, “Mimenu” can mean both “From him”, and “From us”.

As for Ra’avad’s general “tone”, read the ‘back and forth’ dispute by letter between Ra’avad and Razah (regarding Bava Metzia 98b). It is partially quoted in “Shitta Mekubetzes” (ibidem), as it appears in a separate book known as “Divrei Rivos” (toward the end) –

אל יקשה בעיניך כל מה שתראה בה כו’

The gist of the Ra’avad’s defense of his attitude is that that is how he normally speaks and he means no offense. The same can be said for nearly all of Ra’avad’s creations.

This understanding also complies with what we know about the Ra’avad’s presumed agreement with Maimonides whenever he does not explicitly differ (as demonstrated further on by Yad Malachi, ibidem). If the Ra’avad is being polemical, why ever would that be the case? [The Chazon Ish himself and others don’t actually impute any such passage as being Ra’avad’s (for obvious reasons) but the general idea of co-authorship is certainly not far from the truth.]

Not incidentally, the Ra’avad was much older than Maimonides (cf. Tashbetz responsa 1:72), and most likely considered Maimonides a student of his. This is strictly Halachically speaking; not that either physically studied under the other’s tutelage.

I should add that the above conclusion also accords with my tradition from my teachers.

Those who have republished Mishneh Torah sans Ra’avad’s comments (such as Mechon Mamre) seem to implicitly view them negatively. Perhaps they ought to reconsider.

For further research, see Rabbi Yosef Kapach’s introduction to Mishneh Torah and the “Mossad” editor’s intro to the Ra’avad’s responsa.

(The translations of Mishneh Torah are directly from Rabbi Eliyahu Touger, here.)